The lines of migrants streaming across the Rio Grande into El Paso seem far away, until they begin arriving by bus and plane in your state. More than 10,000 refugees have arrived in Chicago since the first group was bussed from Texas in August 2022. The numbers may seem unreal, until you learn those migrants are living in police stations, like the one in your neighborhood.

If you are Jonathan de la O, that’s when you call your church into action. “When we saw what was happening, knew we had to help,” he said. Many of De la O’s church family were immigrants themselves not too many years ago.

De la O drove to Precinct 25 to find young men and some families huddled outside with their few belongings, and others inside were sleeping on the floors. They have nowhere to go, and without help, little chance for work.

So the young pastor of Starting Point Church in the Belmont-Cragin neighborhood, a congregation he planted nine years ago for first- and second-generation Hispanics, opened their doors.

“Our facility has spaces that we have used to house mission teams, but I’ve had to call the teams and say we’ve had a change in plans. We have moved the teams into the auditorium, because we need the sleeping space for migrants.”

Portable partitions form a maze of small rooms on the church’s second floor. Most are about 10’ by 10’, with two air mattresses. Others are slightly larger and sleep three. They provide some dignity and privacy for the guests.

One young man said how grateful he was to be at the church. He described sleeping under a staircase at the police station. The overwhelmed facility had nearly 25 people housed in rooms only slightly larger than his new bedroom at the church.

Downstairs, the migrants have access to a clothing closet, showers, and a kitchen to prepare meals and eat together. The pastor described one man breaking down in tears when De la O showed him the food pantry and told him, “This is yours.”

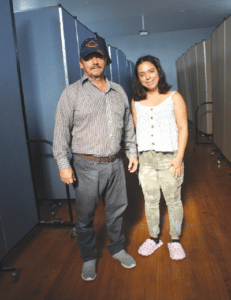

Benardino and his daughter, Franchesca, make a temporary home at Starting Point Church in Chicago.

A young Venezuelan woman, Franchesca, 25, painted a picture of why full shelves bring a grown man to tears. “Because of the dictatorship of the president, there is no food, there is no work, and it is killing the youth,” Franchesca said through a translator. “Everyone that rises up against the government is being killed.”

Franchesca and her father, Benardino, 62, escaped their home in Venezuela through Cúcuta, Colombia. They spent three months mostly on foot traversing jungles, mountains, and then hopping a train for the last stretch through Mexico. Franchesca described the dangers they faced, like holding onto a rope to cross swift-moving crocodile-infested rivers, and avoiding human dangers of robbery and rape in the jungles.

Once at the U.S border with Mexico, they were able to request legal asylum. After about 10 days they were transported to Chicago. The depravation “is something that remains in your mind, the traumas from everything we experienced. But we are so grateful to be here, at peace, now.”

De la O has found help from other churches in the Chicagoland Baptist Association. Elmwood Park Community Church, which recently opened a food bank, regularly supplies the pantry. Real Life Church, which moved into a facility that formerly housed De la O’s congregation, supplied portable air conditioners.

One of the temporary bedrooms at Starting Point Church.

“Our friends at churches in the Association asked what we needed,” the pastor said. “When we told them, they were here right away.”

In the way that crisis becomes opportunity, De la O is finding, too, that opportunity produces some crisis. During the day, he helps the men find work and navigate the immigration system so they can get established in their new home. The plan is for them to stay at the church for a couple of months, then secure housing when they can afford it.

The church, which offered some ministries in English and Spanish, has increased its bilingual worship and Bible study. And De la O is finding his guests, some from Catholic backgrounds, are open to the gospel, because of their open doors.

“I’ll show them their rooms, and I can’t control myself.” De la O admits shedding some tears too. “I go home and tell my wife, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’”

Then he does it again the next day. “It’s overwhelming, but it’s a good thing.”